|

1B: OVERVIEW OF MENTAL CAPACITY LAW IN NEW ZEALAND

38 AC Hughes-Johnson “The Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988: An analysis, commentary and answers to likely questions”. (A seminar by the New Zealand Law Society, October 1988) at 11. 39 Australian legislation, the Victorian Adult Guardianship Act 1987, provided the adult guardianship law model for the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988. 40 In Re S (Shock Treatment) [1992] NZFLR 208 Judge Twaddle declined to order shock treatment therapy for a person with intellectual disability and instead ordered that they live in a community trust home and receive supported rehabilitative therapy. 41 In Re E [1992] 9 FRNZ 393, the Court declined jurisdiction to make a residential care order for a 28- year-old with severe physical disability, as she did not ”wholly” lack the capacity to communicate, and she clearly had the capacity to understand the nature of her decision. In Re “Tony” [1990] 5 NZFLR 609 Judge Inglis declined jurisdiction to make welfare guardian and property orders in respect of a man with schizophrenia who lived in a home described as a “protected environment”, where it was only a hypothetical possibility he might leave. Re A and Others [1993] 10 FRNZ 537, Judge Inglis made an order allowing for the joint appointment of the care centre and a parent for each of five long-term institutionalised individuals with intellectual disability. 42 See for example, Wilson v Wilson [2015] NZFLR 104, where a personal order was necessary to mitigate perceived undue influence for an elderly man with partial incapacity. In Hutt Valley District Health Board v MJP [2012] NZFLR 458 the Court held that it had jurisdiction to order an elderly woman with dementia to reside in a care facility despite her vehement objections. The PPPR Act – an overview

43 Changes to Part 9 of the PPPR Act are discussed below. An EPOA is a grant by a donor when they are mentally capable to another person (the donee) which allows that person to make welfare and/or property decisions when they become mentally incapable or lack capacity for decision-making. 44 There are statutory limitations on substitute decision-makers’ powers; Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, ss 18 and 98. 45 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, ss 8(a) and 8(b). 46 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, s 5. 47 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, s 8(3). 48 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, s 83; Family Courts Act 1980 s 14. 49 Carrington v Carrington (2014) NZHC 869 Katz J at [103]. The parens patriae jurisdiction is expressly contemplated by s 114 of the PPPR Act. Section 17 Judicature Act 1908 applies to “Persons and estates of mentally disordered persons and persons of unsound mind”. See also Dawson v Keesing [2004] 23 FRNZ 493. 50 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, s 18, Limitation on the powers of welfare guardians. In Re W [1994] 3 NZLR 600 the High Court held that it had inherent jurisdiction to declare W’s marriage void on the basis of absence of consent through lack of intellectual capacity. 51 The High Court’s jurisdiction is used where there is withdrawal of life support from incapacitated patients in coma or persistent vegetative state (PVS). The continued existence in New Zealand of the Court’s parens patriae jurisdiction in this context was accepted in Auckland Area Health Board v A-G [1993] 1 NZLR 235, and reaffirmed by the High Court in Re W [1994] 3 NZLR 600 and Re G [1997] 2 NZLR 201. 52 KR v MR [2004] 2 NZLR 847 at [72]. Also reported as X v Y (Mental Health: Sterilisation) [2004] 23 FRNZ 475. 53 KR v MR, above n 52 at [25]. 54 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, ss 12(5)(b), 18(3), 97A(2) and 98A(2). See Chapter 4 Defining Capacity. 55 The factors relevant to deciding capacity are the ability to: communicate choice; understand the relevant information; manipulate the information and appreciate the situation and its consequences (KR v MR at [51]).

56 In the Matter of A [1996] 2 NZLR 354 at 356. 57 See Chapter 5 Best Interests. 58 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, s 65. An application to the Court activates the appointment of a lawyer to represent the “subject person” under s 65 and to report to the Court, among other things, whether the medical evidence supports the Court having jurisdiction to intervene. 59 Ministry of Justice “Guidelines for subject person appointed under PPPR Act, Principal Family Court Judge” (24 March 2011) at www.justice.govt.nz. Where there is a conflict between the wishes of the subject person and what might be considered in a person’s best interests the Court may appoint a lawyer to assist the Court under s 65A. 60 Public Trust v MJD [2013] NZFC 2706. 62 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, ss 86-89. The maximum term of personal orders is three and sometimes five years. 62 See for example, JMG (by her Litigation Guardian AMB) v CCS Disability Action Inc [2012] NZFLR 369, Miller J. 63 E v E, Wellington HC, CIV-2009-485-2335, 20 November 2009. Simon France J. See also JDEB & ors v JAB & RHB and MAB [2013] NZFC 4234, Judge O’Dwyer, following an unsuccessful writ of habeas corpus in the High Court. 64 Examples include: setting in place a procedure on notice to a landlord to make the subject person a party to a tenancy agreement so that support services could be provided to him, JMG v CCS Disability Action, above n 62; facilitating attendance at a hospital so that the mental health patient who lacked capacity to consent to treatment could receive cancer treatment (CD v JMT [2012] NZFC 10147), and transporting a person with severe alcohol dependence to a residential facility to avoid “absconding” Loli v MWY FAM-2009-004-001877, 13 Jan 2011 NZFC Auckland 2011.

The PPPR Act – law reform

65 Above n 62. Above n 62 at [8]. 66 Counsel to assist was appointed by the High Court to consider its parens patriae jurisdiction with regard to JMG who lacked capacity to litigate, but was not subject to any orders under the PPPR Act and who was considered vulnerable. 67 JMG (by her Litigation Guardian AMB) v CCS Disability Action Inc (stay application) Wellington HC, (27 May 2011) Ronald Young J at [20]. 68 Above n 67 at [52]. 69 Law Commission Misuse of Enduring Powers of Attorney (NZLCR, Wellington, 2001). 70 Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, s 93B. See also B Atkin “Schizophrenia and Protection Orders” (1990) NZLJ 204 and discussion on the Part 9 Amendments in S Bell Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act & Analysis (Thomson Reuters, Auckland, 2012) at 36.

71 Letter from Chris Moore (President, New Zealand Law Society) to Claire Kibblewhite (Ministry of Social Development Office for Senior Citizens) regarding the 2007 Amendments to Enduring Powers of Attorney Provisions (5 July 2013) https://www.lawsociety.org.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/69194/l- MSD-EPAs-5-7-13.pdf. 72 Ibid. 73 The report was required by s 108AAB of the PPPR Act 1988. Report of the Minister for Senior Citizens on the Review of the Amendments to the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988 made by the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Amendment Act 2007, Ministry of Social Development, June 2014. 74 Statutes Amendment Bill 2015, Part 21, introduced into Parliament in November 2015. 75 Submission by the New Zealand Law Society on the Statutes Amendment Bill: Part 21 (29/01/2016), http://www.lawsociety.org.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/98207/Statutes-Amendment-Bill,-Part-21-29- 1-16.pdf at [2.7]. The Law Society submitted that the effect of the 2007 changes to the PPPR Act was “an increasing number of people who, for reasons of cost, have not made their own decision about who should be their substituted decision-maker if they lose their mental capacity”. 76 See Chapter 3 Supported Decision-making, and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Family Court statistics

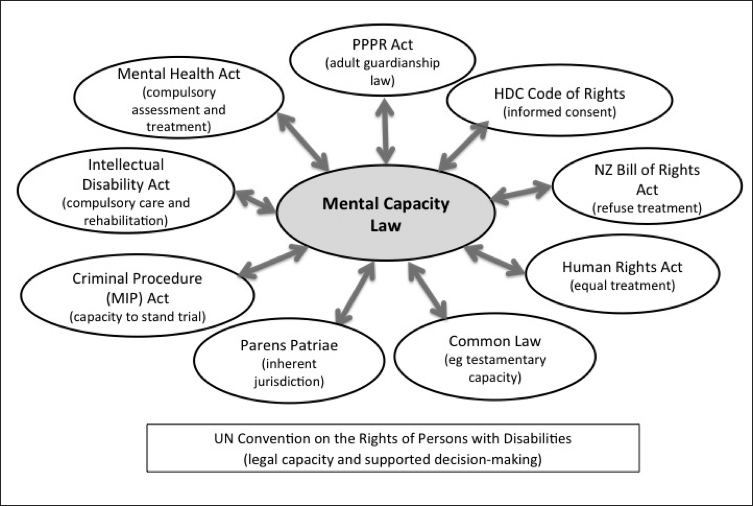

77 Ministry of Justice Reviewing the Family Court: a public consultation paper (Ministry of Justice, Wellington, 2011) at 81. 78 Ministry of Justice Family Court Statistics in New Zealand in 2006 and 2007 (Ministry of Justice, Wellington, 2009) at 57. 79 Unreported Family Court judgments were accessed from the Ministry of Justice but many of these judgments are not on any electronic database. While the process for deciding which judgments will be published aims to become more transparent, there is no “hard data” that can be statistically validated. Furthermore, even where capacity may have been contested, the case may have been resolved through the court-appointed lawyer’s involvement or for reasons unknown. 80 The review was limited by the small sample size and what information can be ascertained from the combined reported (41) and unreported (94) cases. 81 Even where capacity may have been contested, the case may have been resolved through the involvement of the court-appointed lawyer. 82 There are few reports of judges visiting the person in their care setting or on a hospital ward, an approach used for reviews and hearings under the MH(CAT) Act. It is common and appropriate for judges to engage in informal discussion with the subject person and to encourage them to participate, where possible. Mental capacity law in New Zealand Figure 1: Mental Capacity Law in New Zealand

83 Judicature Act 1908, Schedule 2 High Court Rules, Part 4 subpart 7; and District Court Rules 2014, Part 4 subpart 7. 84 A recent report on claimants’ experiences with the ACC appeal process does not address for example, problems ACC encounters in case management for claimants with diminished capacity for decision- making during the claims process: Acclaim Otago Understanding the Problem: An analysis of ACC appeals process to identify barriers to access to justice for injured New Zealanders (Acclaim Otago and University of Otago Legal Issues Centre, Dunedin, 2015). 85 Children, Young Person and Their Families (CPYF) Act 1989, s 108; Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, s 6(2). See AJ Cooke “State Responsibility for Children in Care” (PhD Thesis, University of Otago, 2014) http://hdl.handle.net/10523/4796; Personal communication from L Harrison, (former Barrister) (Dunedin, 2015). 86 Crimes Act 1961, s 138. 87 Crimes Amendment Act (No 3) 2011, ss 151, 195 and 195A create criminal liability for failure to provide necessaries of life, or protect from ill treatment or injury to a child or a vulnerable adult. Section 2 of the Crimes Act 1961 defines a “vulnerable adult” as a person who is unable, by reason of detention, age, sickness, mental impairment, or any other cause to withdraw himself or herself from the care and charge of another. The definition of “vulnerable adult” does not specify an age threshold, but it is presumed to refer to persons over 18. 88 Domestic Violence Act 1995, s 11. See for example, AR and Anor v RDH FC Christchurch FAM-2008- 009-002784. 89 Contraception Sterilisation and Abortion Act 1977 and the Alcohol and Drug Addiction Act 1966. This latter legislation is due to be repealed: Substance Addiction (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Bill 2015. 90 Mental Capacity (Compulsory Care and Treatment) Act 1992; Intellectual Disability (Compulsory Care and Rehabilitation) Act 2003; Criminal Procedure (Mentally Impaired Persons) Act 2003. Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 (MH(CAT) Act)

91 [2012] NZFC 4432, Judge C P Somerville. 92 J Skipworth “Should Involuntary Patients with Capacity Have the Right to Refuse Treatment” in J Dawson and K Gledhill New Zealand’s Mental Health Act in Practice (VUP, Wellington, 2013) at 218. See also Lepping, Stanly and Turner, above n 29 and discussed in Chapter 1A of this report. 93 See Chapter 3 − Liberty Safeguards, for discussion of the interface between MH(CAT) Act and the PPPR Act. 94See W Brookbanks ”Further Reform of Unfitness to Stand Trial” in Dawson and Gledhill, above n 92 at 321. 95 Criminal Procedure (Mentally Impaired Persons) Act 2003, s 24(2)(b) (detention in a secure facility of a defendant found unfit to stand trial or insane as a special care recipient) and s 25(1)(b) (orders declaring a defendant found unfit to stand trial or insane as a care recipient to receive care under a care programme). 96 Intellectual Disability (Compulsory Care and Rehabilitation) Act 2003, s 29 allows a manager of a prison (in the case of a serving prisoner) or the Director of Area Mental Health Services (DAHMS) (in the case of a former special patient) to apply for an assessment if there are reasonable grounds for believing that the person has an intellectual disability. 97 Intellectual Disability (Compulsory Care and Rehabilitation) Act 2003, s 7(1); s 7(5) states that the developmental period of a person “generally finishes when the person turns 18 years”. Evidence now shows that cognitive development takes place at least until the mid-20s, and is dependent on a person’s developmental environment. Often care recipients who been raised in a developmentally deprived circumstances will show significant improvement in cognitive functioning. This has already resulted in some care recipients no longer meeting the criteria of intellectual disability and under s 8(2), the IDCCR Act does not apply. Email from Anthony Duncan (National Advisor to the IDCCR Act, Ministry of Health) to A Douglass regarding the IDCCR Act (7 October 2015). 98 Intellectual Disability (Compulsory Care and Rehabilitation) Act 2003, s 46. 99 For example, in a case where the writer represented the care recipient, the initial assessment undertaken in the criminal court was based on reports 12 years prior and there had not been a reassessment of the care recipient’s adaptive functioning for the purpose of bringing the person under the IDCCR Act regime. 100 Ministry of Health Guidelines for the Role and Function of Specialist Assessors under the Intellectual Disability (Compulsory Care and Rehabilitation) Act 2003 (Ministry of Health, Wellington, 2004) at 5−6. These guidelines have not been reviewed since originally published and the measures for predictive risk have not been translated into the New Zealand context. 101 Regional Intellectual Disability Care Agency Central v VM [2012] BCL 398; [2011] NZCA 659 at [92(a)]. The appeal upheld a High Court decision, VM v RIDCA Central (Regional Intellectual Disability Care Agency) HC Wellington CIV-2009-485-541 (Simon France J). In both VM and another High Court appeal, L v Regional Intellectual Disability Care Agency Central HC Wellington CIV-2010-485-1279 (Mallon J), the care recipients were women in their mid-forties who had assaulted and threatened violence against their caregivers. Prior to being under compulsory care orders they had largely lived in the community with supported care. 102 W Brookbanks “Managing the challenges and protecting the rights of intellectually disabled offenders” in B McSherry and I Freckleton (eds) Coercive Care: Rights, Law and Policy (Routledge, Abington Oxon, 2013) at 219. 103 RIDCA Central (Regional Intellectual Disability Care Agency) v VM [2010] NZCA 213 at [16].

104 Email from Anthony Duncan, National Advisor in the IDCCR Act 2003 regarding the IDCCR Act (7 October 2015). 105 Mirfin-Veitch, Gates, Diesfeld and others, above n 21 at viii. This study recommended that there needed to be mandatory training for individuals representing clients under the IDCCR Act. 106 Justice S Glazebrook “Foreword” in Dawson and Gledhill, above n 92 at 9. It is estimated that some 64 percent of prisoners have experienced a head injury. The extent of prisoners having impaired decision- making capacity is unknown. For example, the writer represented a prisoner before the Parole Board with dual disabilities (mental health and intellectual disabilities) who was subject to an indefinite sentence of periodic detention but whose disabilities only became apparent when in prison. 107 The HDC Code is set out in Appendix C. Right 5 is the right to effective communication; Right 6 is the right to be fully informed; and Right 7 is the right to make an informed choice and give informed consent. Section 11 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 provides that everyone has the right to refuse to undergo medical treatment. The word “everyone” has been interpreted to mean every person who has capacity to consent: Re S [1992] 1 NZLR 363, although this interpretation would now be called in question with the modern notion of legal capacity under the CRPD. 108 In Bedford [2013] NZCorC Decision No. 43/2013, the Coroner commented that no capacity assessment was undertaken when the patient (under the MH(CAT) Act) with Korsakoff’s dementia refused insertion of a nasogastric tube for a hernia repair operation and subsequently died. 109 The terms “capacity” (PPPR Act) and “competence” (HDC Code) are used interchangeably in the relevant legislation. 110 PDG Skegg “Presuming Competence to Consent: could anything be sillier?” (2011) 30 U Queensland Law J 165. 111 Health and Disability Commissioner: General Practitioner Dr C, 11 HDC00647. 112 The doctrine of necessity and Right 7(4) is discussed below in Chapter 3 Liberty Safeguards and Chapter 6 Research on People who Lack Capacity.

These regulatory gaps are described as “liminal” (the spaces in between). They often exist outside existing formal legal and social structures, and are often in a state of flux. Citizens who also experience flux in their capacity can find themselves in liminal regulatory spaces where at times laws might, or might not, apply to them. 113 Letter from Chris Moore (President, New Zealand Law Society) to Claire Kibblewhite (Ministry of Social Development Office for Senior Citizens) regarding the 2007 Amendments to Enduring Powers of Attorney Provisions (5 July 2013) https://www.lawsociety.org.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/69194/l- MSD-EPAs-5-7-13.pdf. 114 Negligent failure to obtain informed consent was previously a ground for medical misadventure but is no longer since the introduction of treatment injury provisions in the Accident Compensation Act 2001, as amended in 2005. 115 Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994, s 14(e). The Commissioner can investigate potential breaches of the HDC Code on a complaint or on his own initiative. 116 Email from Chris Moore (President, New Zealand Law Society) to the Health and Disability Commissioner regarding Review of the HDC Act and Code (17 February 2014) https://www.lawsociety.org.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/75999/l-HDC-Act-and-Code-Review-17-02- 14.pdf. 117 Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994 s 30 sets out the functions of advocates, which includes ensuring that consumers are aware of their rights under the HDC Code and to provide assistance to ensure that healthcare procedures are performed with informed consent of the consumer: s 30(d). Health advocates can also receive complaints and assist persons who wish to pursue a complaint. 118 B Atkin “The Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988 − Update and Reflections” (2013) 44 VUWLR 439. 119 These regulatory gaps are described as “liminal” (the spaces in between) in socio-political literature. Liminal spaces are realms of possibility and transition. Interview with Professor Graeme Laurie, Chair of Medical Jurisprudence and Director of the JK Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Sciences and Law, Edinburgh University (A Douglass, Edinburgh, 29 May 2015). |